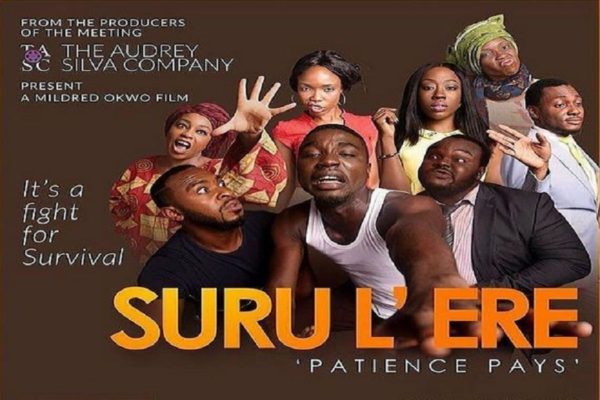

The film Suru L’ere, directed by Mildred Okwo,

provides a reviewer with a rather unusual problem. Ninety percent of

the film is watchable, enjoyable even, and every flaw in those parts,

are excusable or even reasonable. This happens with many films and is

hardly a problem. If you want perfection, go watch paint dry.

The trouble is the other ten percent comes at the end and negates all that has gone before.

Suru L’ere is about Lagos as it happens to one man. Arinze (Seun Ajayi)

is a man working for the most deadpan cruel boss ever. He owes the

landlady, who’s given to singing songs about his indebtedness, he owes

the local medicine seller. He needs some sleep. He is living the meager

life of a Lagos hustler. Except Arinze is no hustler. His boss Brume

sums his plight: “…there’s no space at the top for lookers,”. When a

comedy of errors presents him with chance to make a fast buck, he takes

it. The only problem is he really intends to do the job given to him by

the rich, lazy, beautiful Omosigho (Beverly Naya).

Nollywood actor Seun Ajayi doesn’t look

like a leading man; his only star power is his smile. But he makes up

for that lack with the quality of his acting. Good thing he is in nearly

every frame. At first he is too good for the other actors. His boss (Gregory Ojefua)

looks like a tractor and speaks like a robot. Beverly Naya doesn’t know

what to do to hold a scene alone. The first problem is solved when you

realise that his boss is indeed a robot, as driven by the same things as

the robots working for him. (This is a sympathetic reading that the

film will destroy later)

The second problem is handled in the

redemption of Beverly Naya’s self-consciousness by the unlikely and yet

present chemistry between herself and Seun Ajayi. They share a great

romantic scene, which has to be the first time, in film or in real-life,

where anyone falls in love over a plate of semovita.

As said, Seun Ajayi is not built like a

star. What he has isn’t exactly an everyman-ness—it is an

every-Lagosian-ness. Not the mannerism of someone who is going to

conquer the city but someone who has been dominated by the city. Early

mornings you can see both types of persons in any queue for a BRT bus.

You know the guy who is sweating and looking in the distance earnestly?

That is Arinze.

Seun Ajayi’s shoulders slump forward as

Arinze walks in deference of his circumstance, and more than once he

runs. Like every Lagosian he’s in a hurry. It’s excellent casting. You

can’t see a Ramsey Nouah in the role. OC Ukeje perhaps—but in that case the unseemly attraction between Arinze and Omosigho, which is part of Suru L’ere‘s

charm, would be gone. It is also why the explanation of the error that

leads to their meeting isn’t believable. But then, to use a super-hero

equivalent, that no one can tell that Clark Kent and Superman are same

persons isn’t believable either.

Broadly speaking, the superhero movie

and the comedy are working on the same premise: they are making a

promise. The modern superhero movie asks that in return for the

excitement of a showdown you hand over your disbelief. The comedy asks

for your incredulity and connivance in return for a laugh. In other

words: What works for superhero movies is an impending excitement; what

works for comedy is an impending hilarity. Give me your disbelief, both

genres say, and I’ll show you a good time. That exchange may be the

entire basis upon which every fictional art is based.

What ruins that good time is if the joke

doesn’t come off or the showdown is an anti-climax. Or worse: if the

filmmaker reverses—proving the viewer a fool in suspending disbelief.

This is what happens in Suru L’ere. In a bizarre twist the

robot boss, whose deadpan face becomes useful to the film’s laughs, is

revealed to have had some sentimental problem in the past. The

experience transformed him. It is too easy and such a cliché that you

want your disbelief back with interest.

After the viewer has accepted his

character as a deliberate caricature, put in place to emphasize the

inhumanness of Lagos, she is told that Boss Brume has a fragile heart.

And because he is important to the plot, the core of the film’s comedic

appeal is ruined. What has been attributed to the screenwriter’s

expertise is revealed to have been performed unwittingly.

To re-use the superhero example: It’s

like finding out that Superman isn’t the reporter Clark Kent but the

office messenger. A charitable soul might say the goal is misdirection

like with magicians. But a magician’s act depends on emphasizing his

skill not pissing off the audience. For the latter to be taken in good

faith, the former has to be beyond reproach. That doesn’t happen in Suru L’ere. It merely turns out that the audience was wrong to hand over disbelief.

From that point the film crumbles: A side-story involving an effeminate character (played delightfully by Tope Tedela)

is dropped perhaps because the writer couldn’t quite figure what to do

with it. Someone must have realized what was happening – that the film

was going heavy when it should be light. Mildred Okwo’s earlier feature The Meeting

played light. Writing about that film a few years ago, I noted that the

true ground-breaking story would have been to make the considerably

older character in that film’s central relationship female. But it

didn’t have to. The Meeting was comfortable betting small.

Suru L’ere bets small as well.

But you see the hands of a director reaching for something big when the

material is content to remain small. You see the director abandon the

bid for weight halfway and wonder why the attempt in the first place.

What was advertised was a comedy, what we get is a rather simplistic

morality play: lazy girl loses, fat guy gets a heart attack, poor dude

gets cash.

Still, nothing is as irksome as the

twist-that-ruins-everything, which has become a rather disturbing trend

of modern Nollywood. No one seems to be able to make a good film out of a

linear sans twist. Road to Yesterday embarked on a psychological twist. Gbomo Gbomo Express employed a thriller-ish one. Champagne applied a deranged one. Out of Luck used an incoherent one. Suru L’ere

doesn’t quite use a conventional twist; it uses a narrative one. Like

all of the others mentioned here, the use is questionable.

While everyone worried about Nollywood’s

progress seem to have a tunnel vision for its aesthetics and production

values, which are improving, there’s a troubling homogeneity taking

place at the level of the story. Every film now wants to employ twists

in the last third. Have all of our filmmakers attended the same film

school? and yet, by how much can a twist be said to be surprising if

every filmmaker uses one with minor deviations? Is it still a twist if

every viewer is certain that around the hour mark, something predictably

‘shocking’ will happen?

“Drama,” says a character in Suru L’ere, “every family has theirs.”

“Twists,” responds the audience, “every Nollywood film now has one.”

courtesy: BellaNaija

No comments:

Post a Comment